Quote:

Originally Posted by arghx7

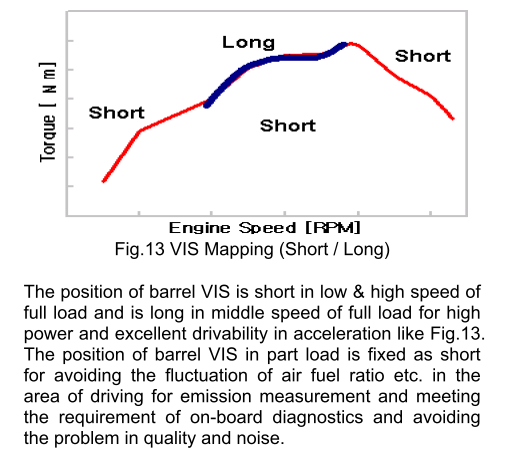

One of the things that really makes intake and exhaust manifolds complicated are variable cam phasers (VVT). Here's a case-in-point, the 2.4L direct injected nonturbo engine on the Hyundai Sonata. This engine has variable cam timing on both intake and exhaust, as well as a variable intake runner system:

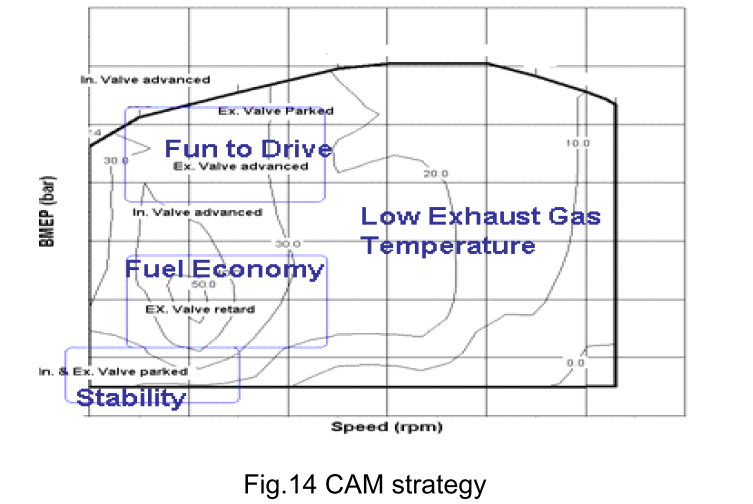

As counter-intuitive as it may seem, it actually runs short intake manifold runners at low speed and longer runners only in the mid range. Here is a cam timing map for that engine using isobars:

|

I think a lot of the 'Long runner= low-end power' and 'short runners = top-end' has to do with the fact that they didn't have cam phasing back then.

It likely has to do with which wave reflection they were tuning for.

On a short runner it may be possible to get a positive wave on an early reflection at low rpm, but probably at the expense of corresponding negative wave a little later in the power band. What the cam phasing can do is change when the valves open/close/overlap related to when the good and bad pressure waves come back.

With a longer runner but unable to change cam phasing, maybe to get the low/mid rpm positive wave boost, the later negative reflections will only come back at an rpm higher than the motor runs. So with cam-phasing this can be tuned around now.

Fat power bands are becoming the norm now, which is why I don't believe the brochure torque number is a peak one. An example is the LFA with two stage intake induction. It makes 90% of peak torque from 3700 rpm to probably its redline. (At the minimum a bit past its 8700 rpm power peak.)